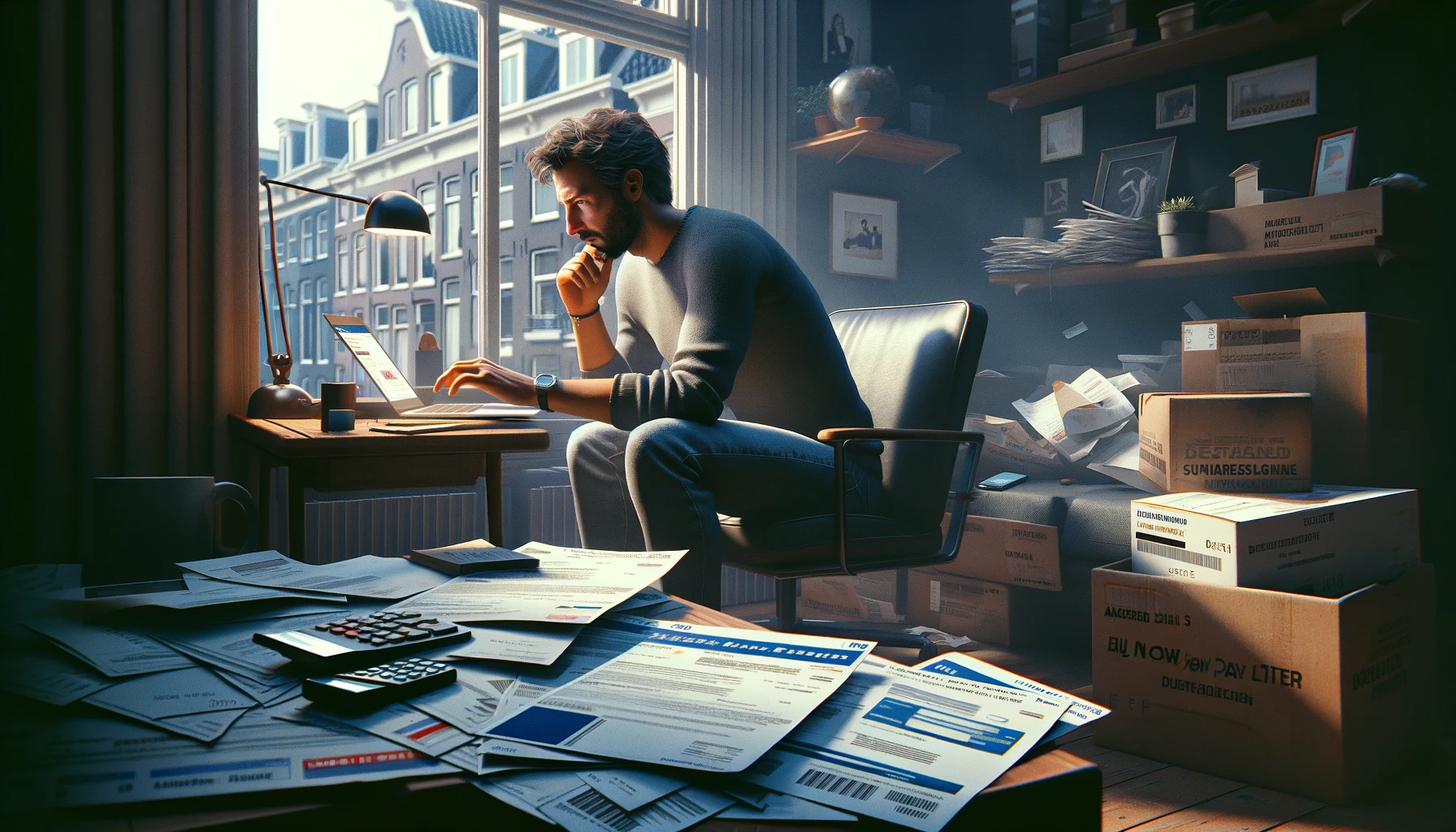

More and more Dutch online shops are offering customers a ‘Buy now, pay later’ button from companies such as Klarna and Riverty (formerly Afterpay). With this, Dutch people place tens of millions of orders every year without checking out. H&M calls it a ‘modern shopping experience‘. The temptation not to pay appears to be great and profitable, as one in five Dutch people regularly make unnecessary purchases as a result. But the ‘modern shopping experience’ goes further: because one in five customers also do not pay on time, their shopping experience also consists of high fines and collection agencies. According to the AFM, these collection practices account for 20 to 40 per cent of the turnover of pay-later companies. Those who think these companies have to comply with strict legislation are in for a surprise: ‘pay later’ is not legally a loan, so less strict rules apply and these companies do not fall under AFM supervision.

As it was found in the past that minors were also using the ‘buy now, get in trouble later’ button, providers agreed in a code of conduct to ask customers for their date of birth to ‘check’ whether they are of age. But what was to be expected happened: minors simply fill in a different date of birth and can still get into debt. That is why a fortnight ago VVD and ChristenUnie came up with a proposal calling for the introduction of an identification requirement for all millions of customers of these pay-later companies to check the customer’s age. A week later, it was revealed that copies of passports of thousands of Dutch citizens were stolen and offered on the dark web, and that a Dutch grandfather is taking a Belgian gambling company to court because his grandson (17) gambled away half a million euros of his money. The boy had his way because he had swiped his grandfather’s PIN numbers and used a copy of his father’s passport to pretend to be an adult.

The proposal by the VVD and ChristenUnie for online shops and their ‘pay later’ providers to process more personal data to more accurately determine the age of their customers, however well-intentioned, will also create new privacy risks. Moreover, the example of the 17-year-old boy shows that such measures are easy to circumvent, as we know from other sectors where age limits have been introduced: research by the NVWA shows that it is ‘not difficult‘ for minors to get tobacco products. Moreover, the identification requirement is likely to exacerbate the problems by encouraging minors to place orders without paying in the names of adult friends or family members, with even greater consequences in the likely cases when things go wrong.

So the VVD and Christian Union proposal will not effectively solve the problem. At the same time, it does create yet another privacy breach. We could also do the opposite: protect the fundamental right to privacy and effectively combat the underlying problem. That starts by naming the right problem, which in this case is not at all limited to minors: the revenue model by which shops, which get more and bigger orders, and collecting payment service providers make money from the “modern shopping experience” that entices vulnerable consumers of all ages to overconsume and go into debt. And that problem cannot be solved at all with ineffective identification requirements. On the contrary. By soon asking millions of online shop customers to identify themselves, they become double victims. First, they have to pay with their privacy. And then they put themselves in debt, after which they have to pay a second time, but this time at the collection agency. And minors? They just borrow their father’s passport and place an order in grandpa’s name, as they already do now.

This article appeared today in daily newspaper Trouw.

Leave a Reply